Civil War Pictures page 5

Sergeant Cornelius V Moore

Sergeant Cornelius V. Moore of Company B, 100th New York Volunteers, a sergeant of 39th Illinois Regiment, a corporal of 106th New York Volunteers, and a private of the 11th Vermont Regiment .

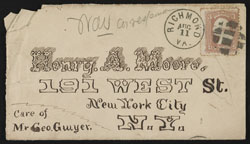

He was was twenty years old when he enlisted as a Union soldier in the American Civil War, joining the 100th New York Infantry, alongside his older brother Edward. An artist by occupation, he kept a record of his and Edward’s adventures and sufferings throughout the war by means of illustrated letters sent home, in envelopes with elaborately lettered addresses, to another brother, Henry.

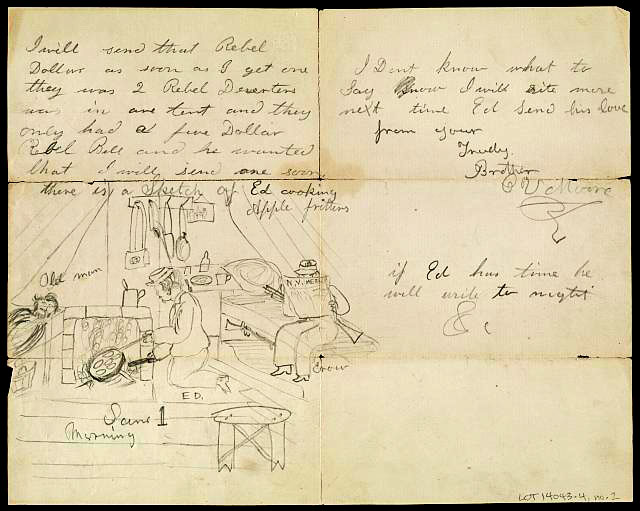

Cornelius and Edward joined the army without much knowledge of how long they would be kept at war. “I hope you will find out whether we got to stay 3 years or 9 months,” Cornelius wrote in a letter soon after enlisting, dated January 13th, 1863. They were stationed at Morris Island, South Carolina, which he would later describe, likely ruefully, as having “no trees, nothing but white sand.” The winter seemed fairly pleasant for the not-yet-endangered men. The savvy Cornelius had quickly found a business venture in the camp, and was “making money hand over fist selling things.” The regiment had enjoyed corned beef and plum pudding for Christmas dinner, and Cornelius included a drawing of Ed cooking apple fritters in the tent.

Letter and drawing by Cornelius More 1863

Letter and drawing by Cornelius More 1863

Cornelius’s letter of March 5th showed that romantic drama reached the men even at war in the deep south. “Ed got the Valentine but you must not say anything about it,” he wrote. “It had Sarah’s name on it. I did not read that letter which Sarah sent Ed but Ed read it and said that he would not answer it.”

The Moores’ company was detached from the regiment, so they were able to avoid picket duty. “We don’t have any thing to do but to paint,” reported a grateful Cornelius, who also included a wry sketch of an incoming cannon ball threatening to knock over the paint cans.

The summer and fall passed without much incident for the Moores. “Every thing is quiet down here,” wrote Cornelius on December 22nd. The men were still in the dark about the service they owed. “Do you hear any thing about the drafted men being only for nine months?” wrote Cornelius, more than nine months after his enlistment. “If you hear anything about it let us know. The talk in camp is that the regiment will be in Buffalo by the 4th of July. We can’t tell how true it is.”

The rumors were false. Cornelius’s next letter, of November 27th, 1864, brings news of a sharp change in the men’s fates. They were both taken prisoner at Drewry’s Bluff, Virginia, on May 16th. Cornelius was taken to infamous Andersonville, Georgia. For the first four months, including a twenty-two day stretch of rain, he and his fellow prisoners were kept in a stockade, with “no shelter but the Heavens above us.” Food was a piece of cornbread, a square inch of pork, and occasionally a few spoonfuls of rice. Edward had been sent to the prison at Milan, Georgia. Forced to subsist under equal or worse conditions, he died on October 29th. Disease was the culprit in the official record; exhaustion and starvation in Cornelius’s account.

Cornelius had been paroled on November 20th. “I thought I would never see you again but there is hope now,” he wrote in the letter. The artist who had sent the droll sketches now relayed the tragic news of his brother’s death in a shaky hand. “I can’t hardly write, this is the first time I had a pen in my hand since I was taken prisoner.”

By March of 1865, Cornelius had returned to the 100th regiment, now stationed at Richmond, Virginia, in the 24th corps of the Army of the James. That winter, Cornelius was promoted twice, to Corporal and then Sergeant, and his corps enjoyed an increase in rations and the respect of officers and soldiers from both armies. A rebel soldier, noticing that the badge of the 24th corps was emblazoned with a heart, remarked to Cornelius that “hearts was trumps.” Even General Robert E. Lee, according to Cornelius’s letter home, “said that Grant could be well proud of the 24th corps.”

After the Confederate surrender, Cornelius Moore and his corps received heroes’ welcomes back into Richmond. Wrote Moore on April 26th:

After the Confederate surrender, Cornelius Moore and his corps received heroes’ welcomes back into Richmond. Wrote Moore on April 26th:

The soldiers that was in Richmond was all formed in line along the gutters of the side walk to receive us. They played the bands of every reg’t as we walk by them. It was nice to see the folks in Richmond and the stores all open selling everything.

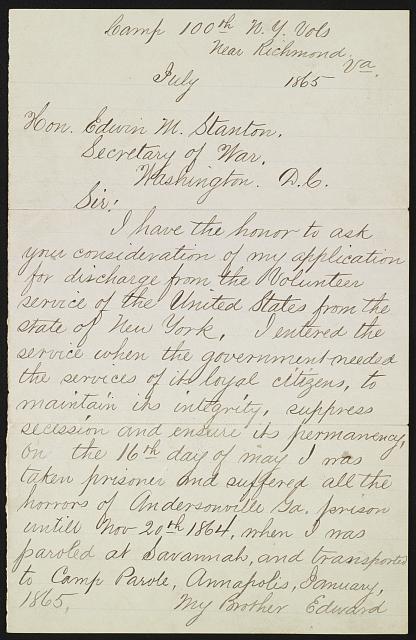

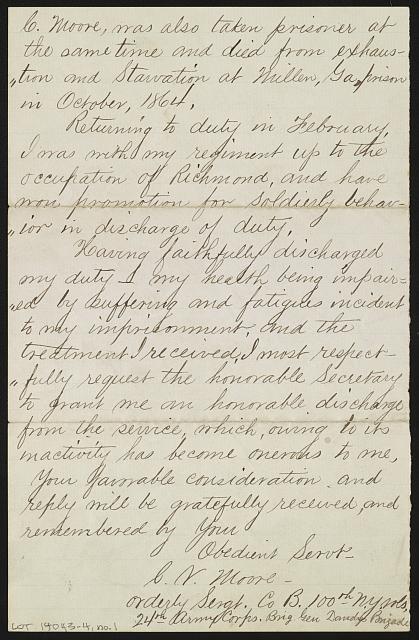

The corps dutifully waited for the repair of the railroad that would take them to Washington and eventually home. But nothing happened quickly. Three months after the surrender and the fanfare in Richmond, Cornelius was still in Virginia with his regiment—though with another promotion, to First Sergeant, to his credit. Still seeking an answer to the question he had been asking for two years, he queried a higher authority than camp rumors—he wrote to Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, requesting an honorable discharge.

Letter, Cornelius Moore to Sec. of War Edwin Stanton, 1865 July.

“I entered the service when the government needed the services of its loyal citizens, to maintain its integrity, suppress secession and ensure its permanency,” he wrote. But the war’s end had made fighting for these ideals no longer necessary, and Cornelius felt he had fulfilled his duty, evidencing his months of suffering “all the horrors of Andersonville,” his brother’s death, and his dedication to his regiment in its subsequent occupation of Richmond. “The service…owing to its inactivity has become onerous to me,” he admitted.

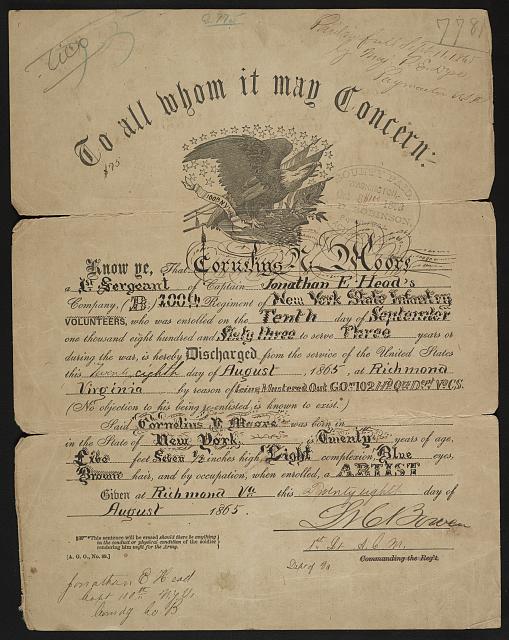

Perhaps Stanton intervened. Either way, Cornelius Moore, “Occupation: Artist” written in intricate lettering, was finally discharged from the United States Army on August 28, 1865.

Discharge form for Cornelius More, 1865

Discharge form for Cornelius More, 1865

Compiled by: Ann Tyler Moses.

Continue

Leave a comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.